fMRI lie detection evidence, supplied by the company No Lie MRI, has been considered during pre-trial criminal hearings in the USA, this time in the case of Gary James Smith v. State of Maryland [1, 2]. The device has already had a couple of hearings as potential evidence, with tests conducted by rival company Cephos, first in New York [1, 2] in 2010 and then again in Tennessee [1, 2, 3, 4] later that year.

Gary Smith is accused of shooting Mike McQueen in 2006 and is about to go to trial for the second time, after the Court of Special Appeals affirmed the verdict of the trial court, and then the Court of Appeal reversed and ordered a retrial. The first verdict, which had found him guilty of second degree murder (or ‘depraved heart murder’) was overturned on the basis that the trial court had admitted prosecution evidence of the decedent’s ‘normal’ state of mind, but hadn’t allowed evidence to the contrary.

The case is an interesting and complex one, particularly as regards medical and scientific evidence. For a start, both Smith and McQueen worked as Army Rangers and served in the ongoing conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq. As such, both parties, the defense and the prosecution, claim that post-traumatic stress is, in part, to blame for the tragedy. In the first trial, the prosecution suggested that Smith’s PTSD may have left him unstable, which may have contributed to him murdering McQueen, whilst the defense argued that McQueen’s PTSD led him to commit suicide. The case thus quickly became a focal point for a still ongoing debate over the hidden psychological and medical costs of the war on terror. Furthermore, two experts appointed by the court were divided over the blood spatter evidence, with one claiming it suggested suicide and another that it pointed towards murder.

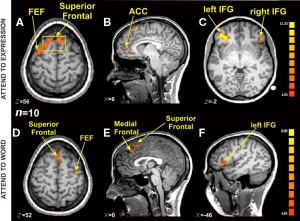

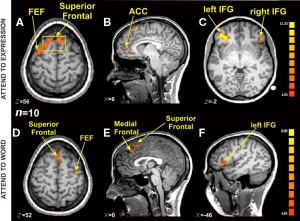

Moreover, as part of his pre-trial hearing with Judge Eric M. Johnson, of Montgomery County Circuit Court, Smith recently sought admissibility for fMRI evidence of the veracity of his claim that he did not shoot and kill McQueen. The evidence, though the judge found it ‘fascinating’, was excluded. The decision appears to have been founded on the current lack of evidence that the device works as a lie detector, said Judge Johnson: “There’s no quantitative analysis of this procedure available yet.” In contrast, Joel Huizenga, CEO of No Lie MRI, said: “There is always room to do more research in anything, the brain’s a complex place. There have been 25 original peer reviewed scientific journal articles, all of them say that the technology works, none of them say that the technology doesn’t work…that’s 100 percent agreement.”

It shouldn’t be a surprise that community opinion has again been influential in determining admissibility of scientific evidence regarding veracity, it has long been so, particularly since the long-established Frye ‘general acceptance’ rule was decided on the same basis in the case of the exclusion of the polygraph, nearly one hundred years ago. However, proponents of fMRI lie detection, such as Steven Laken, CEO of Cephos, have argued that lie detectors are held to a higher standard than are other forms of scientific evidence: “But the standard is set even higher for these lie detectors because of this idea that the judge or the jury are basically the final determiners of whether someone is lying on the stand…The courts are unfairly putting a higher bar on that than they are on other scientific evidence like DNA.”

Expert testimony, like that of the gun splatter expert, gets enmeshed in legal talk in unpredictable ways. Various technologies are enrolled to understand the significance and reliability of new techniques under consideration. Indeed, the polygraph – for instance – has often been compared to fingerprinting or DNA evidence when deciding on its admissibility. The difficulty that those supporting fMRI lie detection face is in seeking to make it amenable to a complex system in which notions of responsibility, guilt, lying and truth are constantly at play between rules, precedents, expert evidence and legal talk during trials. Take, for instance, the following quote from the closing statement of the prosecution in the first trial of Gary Smith:

“It’s been 18 months since Michael McQueen was buried. This defendant shot him. It’s time for justice. Healing begins when justice occurs. And the only just verdict in this case, the only proper verdict in this case is to hold that person responsible for [what] the physical evidence shows, no matter what experts you want to believe, that he was right there when he was shot. What your common sense and understanding shows [is] that you don’t stage a scene, you don’t throw away a gun, you don’t lie and lie and lie and lie to the police, unless you’re guilty as sin.”

This decision seems, on the face of it, to be a further defeat for the corporations seeking to admit fMRI lie detection evidence. However, advocates of exclusion, such as the eminent law professor and scientifically well-informed Hank Greely of Stanford Law School, whose testimony has been influential in these early cases, might be wise not to rest on their laurels. There are likely to be more, and perhaps more significant, spaces in which the battle over fMRI lie detection will be fought. Importantly, however, these are not as easy to pin down as the criminal trial courts. Lessons from the history of the polygraph regarding its entanglement with governance teach us that exclusion from criminal trial courts is far from the end of the story as goes lie detection.

The rhetorical construction of the polygraph as the lie detector contributed to its being adopted in a wide range of spaces in the USA. For example, the polygraph continues to be used in the context of employee screening, espionage, police interrogations and private investigation. Or take one further example: paedophilia. In a week or so I’ll be reporting on the use of the polygraph machine in the context of sex and criminal sexual behaviour, where it is now commonly used in the USA to manage paedophiles during post-conviction probation. Such use of the polygraph was recently trialled in several UK regions and looks set to be taken-up more broadly. As such, even though the device was barred from criminal courts in Frye, the polygraph has since been used in very particular, but also very important, legal spaces close, but just outside of the trial.

fMRI appears to be going the same way. The No Lie MRI website boasts that: “The technology used by No Lie MRI represents the first and only direct measure of truth verification and lie detection in human history!” This rhetoric of direct measurement has been a key one in the articulation of the fMRI machine’s potency for lie detection. Constituting the brain as the location of truth and thus of lying, the fMRI researchers have frequently claimed that we are looking directly into the lie. This has been used to help position the fMRI machine as the natural successor to the polygraph by positing it as a technological improvement on the polygraph’s indirect measurement. No Lie MRI claims: “lie detection has an extremely broad application base. From individuals to corporations to governments, trust is a critical component of our ability to peacefully and meaningfully coexist with other persons, businesses, and governments.”

Irrespective of whether the technique ‘works’, more attention should be paid to the complex way in which lie detection evidence is negotiated in relation to medical diagnoses, like PTSD, and other technologies such as blood spatter, DNA or the polygraph. Moreover, we have to better understand how lie detection techniques have dispersed into the US (and now into other countries, such as here in the UK), how they are used and what their consequences are, in order to better respond to fMRI’s emergence as a lie detector. Otherwise, fMRI may be excluded from criminal trials in much the same way as the polygraph but still find use in a variety of significant social, legal and political spaces that are far more difficult to control. The fMRI machine looks new and shiny but as regards lie detection, it might all be a little bit of history repeating.

Chapter 8 reviews the ways in which uncertainty in lie detection has figured in its techno-legal configurations within socio-legal situations. It explores the implications of this account for developing a sociological approach to lying, drawing on key insights from Georg Simmel and others, and indicates why these need to be revised to reflect today’s biopolitical schemes of social order, and to address the complex struggles over information and truth in contemporary sociotechnical systems and ‘post-truth’ politics.

Chapter 8 reviews the ways in which uncertainty in lie detection has figured in its techno-legal configurations within socio-legal situations. It explores the implications of this account for developing a sociological approach to lying, drawing on key insights from Georg Simmel and others, and indicates why these need to be revised to reflect today’s biopolitical schemes of social order, and to address the complex struggles over information and truth in contemporary sociotechnical systems and ‘post-truth’ politics.

These and a great many more small changes in the discourse of crime and the body helped to consolidate the idea that some technique or technology could be used to access the internal state of a criminal suspect resistant to interrogation. Practitioners of applied psychology, developing their work most fervently from the 1870s onwards, produced a central set of technologies that examined psychic states by monitoring physiological changes. The years from 1870 to 1940 thus saw the development of numerous lie detection devices such as truth serum,

These and a great many more small changes in the discourse of crime and the body helped to consolidate the idea that some technique or technology could be used to access the internal state of a criminal suspect resistant to interrogation. Practitioners of applied psychology, developing their work most fervently from the 1870s onwards, produced a central set of technologies that examined psychic states by monitoring physiological changes. The years from 1870 to 1940 thus saw the development of numerous lie detection devices such as truth serum,

We are in a period in which child sex offences cause moral panics and thus help further the measures we are willing to take in punishing and policing them. Laws are passed under the names of the victims to remind us of the cruel and brutal acts committed against children. The media drives up fear and anger because it sells print, and because they know we need an enemy. The paedophile is now the sexual terrorist – his actions undermine the structural organisation of Western society by explicitly challenging the notion of ‘childhood’. This notion is not simply natural consequence of our biology but an entangling of ‘social’ and ‘material’ phenomena. Amongst a number of other causes of the entrenchment of the notion of the innocent child, was the fact that once we had machines and automation in factories, on farms, etc., we no longer needed children to do hard labour. The contemporaneous emergence of psychiatry also welcomed a whole host of ways in which adult sexuality was connected to childhood experience, and thus the fracture of innocence became connected to criminal and deviant behaviour in adulthood. This is not to say that our bodies do not change as we grow older or that our emotional ability to manage relationships both sexual and familial does not similarly develop. Instead, it is to point towards the cultural production of a relation between innocence, sex and criminality that underscores the construction of sex offenders as contemporary monsters and underpins media and moral panics.

We are in a period in which child sex offences cause moral panics and thus help further the measures we are willing to take in punishing and policing them. Laws are passed under the names of the victims to remind us of the cruel and brutal acts committed against children. The media drives up fear and anger because it sells print, and because they know we need an enemy. The paedophile is now the sexual terrorist – his actions undermine the structural organisation of Western society by explicitly challenging the notion of ‘childhood’. This notion is not simply natural consequence of our biology but an entangling of ‘social’ and ‘material’ phenomena. Amongst a number of other causes of the entrenchment of the notion of the innocent child, was the fact that once we had machines and automation in factories, on farms, etc., we no longer needed children to do hard labour. The contemporaneous emergence of psychiatry also welcomed a whole host of ways in which adult sexuality was connected to childhood experience, and thus the fracture of innocence became connected to criminal and deviant behaviour in adulthood. This is not to say that our bodies do not change as we grow older or that our emotional ability to manage relationships both sexual and familial does not similarly develop. Instead, it is to point towards the cultural production of a relation between innocence, sex and criminality that underscores the construction of sex offenders as contemporary monsters and underpins media and moral panics. Against this background, a number of Western strategies of governance in education, sexual health and criminal behaviour can be seen to be geared around securing healthy, happy, playful and above all innocent lives for our children. The corollary of this is the ‘adult’ – the sexually, intellectually, economically mature individual now capable of work, reproduction and decision-making. Challenging the norms of childhood and adulthood, paedophiles are thus not only coded as monstrous because of the acts in which they engage but because their symbolic function is to uphold the binary they seek to destroy. This helps explain our punitive obsession with them and with their bodies. The paedophile is at the far edge in terms of the lengths to which we go to monitor, manage and predict criminal behaviour, and unique in regards to the kinds of treatments and punishments we mete out.

Against this background, a number of Western strategies of governance in education, sexual health and criminal behaviour can be seen to be geared around securing healthy, happy, playful and above all innocent lives for our children. The corollary of this is the ‘adult’ – the sexually, intellectually, economically mature individual now capable of work, reproduction and decision-making. Challenging the norms of childhood and adulthood, paedophiles are thus not only coded as monstrous because of the acts in which they engage but because their symbolic function is to uphold the binary they seek to destroy. This helps explain our punitive obsession with them and with their bodies. The paedophile is at the far edge in terms of the lengths to which we go to monitor, manage and predict criminal behaviour, and unique in regards to the kinds of treatments and punishments we mete out.

Earlier in the year,

Earlier in the year,  Chemical castration and medication are not the only ways that we have found to code, manage and measure the risk of sexual offender’s bodies and desires. Since around the 1980s, the infamous lie detection device, the polygraph machine, has been used in the USA to monitor offenders’ behaviour in post-conviction probation programmes. Checking up on them periodically to ask questions about whether they’ve breached the terms of their probation (Have you have any contact with…?) forms a temporal mode of surveillance, in which the polygraph exam is understood to increase the fear of future discovery. In this respect, we imagine that sex offenders make rational decisions weighing up the costs and benefits of criminal activity in the moment of deviant decision-making.

Chemical castration and medication are not the only ways that we have found to code, manage and measure the risk of sexual offender’s bodies and desires. Since around the 1980s, the infamous lie detection device, the polygraph machine, has been used in the USA to monitor offenders’ behaviour in post-conviction probation programmes. Checking up on them periodically to ask questions about whether they’ve breached the terms of their probation (Have you have any contact with…?) forms a temporal mode of surveillance, in which the polygraph exam is understood to increase the fear of future discovery. In this respect, we imagine that sex offenders make rational decisions weighing up the costs and benefits of criminal activity in the moment of deviant decision-making. These uses of the polygraph are sometimes supplemented with the penile plethysmograph, a device that measures the tumescence of the penis by use of a rubber ring or a volumetric chamber during exposure to various pornographic (both consensual and non-consensual, adult and under-age) materials. The changes in his penis during this exposure are used as a proxy for his desire and thus feed into determining his riskiness. These examinations, like those of the polygraph, ultimately serve to reinforce the notion that the sex offender is fundamentally different, by showing how his body responds differently and by exploring the fine detail of his sexual imagination.

These uses of the polygraph are sometimes supplemented with the penile plethysmograph, a device that measures the tumescence of the penis by use of a rubber ring or a volumetric chamber during exposure to various pornographic (both consensual and non-consensual, adult and under-age) materials. The changes in his penis during this exposure are used as a proxy for his desire and thus feed into determining his riskiness. These examinations, like those of the polygraph, ultimately serve to reinforce the notion that the sex offender is fundamentally different, by showing how his body responds differently and by exploring the fine detail of his sexual imagination.